Multi-modal and Multi-function Transformers

Transformers have gained immense popularity within deep learning and AI communities in recent years. Since their introduction in Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need", they have proven to be powerful sequential models across diverse domains, with thousands of variations and "improved versions." The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs), which largely use Transformers as their foundation, has led to another surge in research around this architecture. This trend has even led graph learning and Computer Vision (CV) communities to move beyond their established foundation models (i.e., GNNs and CNNs) and embrace Transformers. This explains the increasing prevalence of graph Transformers and image Transformers today.

Han et al., “A Survey on Vision Transformer”; Khan et al., “Transformers in Vision”; Yun et al., “Graph Transformer Networks.”

Beyond "chasing the trend," using Transformer as a unified foundation model offers several advantages:

- Transformers excel at capturing long-term dependencies. Unlike GNNs and CNNs which require deeper network structures for longer context, Transformers natively support global dependency modeling through their self-attention mechanism. They also avoid global smoothing and vanishing gradient problems that hinder context length scaling in other network architectures.

- Transformers process sequences in parallel rather than sequentially, enabling full utilization of GPU acceleration. This advantage can be further enhanced with techniques like those described in Dao et al., "FlashAttention."

- Transformers are flexible network structures. They don't inherently enforce sequentiality—without positional encoding, the ordering of input steps to Transformers is equivalent. Through strategic permutation and positional encoding, Transformers can adapt to a wide range of structured and unstructured data.

- The development of LLMs has made many open-weight Transformer models available with strong natural language understanding capabilities. These Transformers can be prompted and fine-tuned to model other modalities such as spatiotemporal data and images while retaining their language modeling abilities, creating opportunities for developing multi-modal foundation models.

- From a practical perspective, using Transformer as a foundation allows reuse of technical infrastructure and optimizations developed over years, including efficient architecture designs, training pipelines, and specialized hardware.

In this article, we will briefly explore techniques for unifying multiple modalities (e.g., natural language and images) and multiple functionalities (e.g., language models and diffusion denoisers) within a single Transformer. These techniques are largely sourced from recent oral papers presented at ICML, ICLR, and CVPR conferences. I assume readers have general knowledge of basic concepts in ML and neural networks, Transformers, LLMs, and diffusion models.

Since images and language modalities represent continuous and discrete data respectively, we will use them as examples throughout this article. Keep in mind that the techniques introduced can be readily extended to other modalities, including spatiotemporal data.

General Goal

The goal of a multi-modal Transformer is to create a model that can accept multi-modal inputs and produce multi-modal outputs. For example, instead of using a CNN-based image encoder and a Transformer-based language encoder to map image and language modalities to the latent space separately, a multi-modal Transformer would be able to process the combination of image and language (sentence) as a single sequence.

.png)

Beyond multi-modal processing, a multi-function Transformer can, for example, function as both a language model (auto-regressive generation) and diffusion denoiser (score-matching generation) simultaneously, supporting two of the most common generation schemes used today.

Modality Embedding

A fundamental challenge in unifying multiple modalities within a single Transformer is how to represent different modalities in the same embedding space. For the "QKV" self-attention mechanism to work properly, each item in the input sequence must be represented by an embedding vector of the same dimension, matching the "model dimension" of the Transformer.

.png)

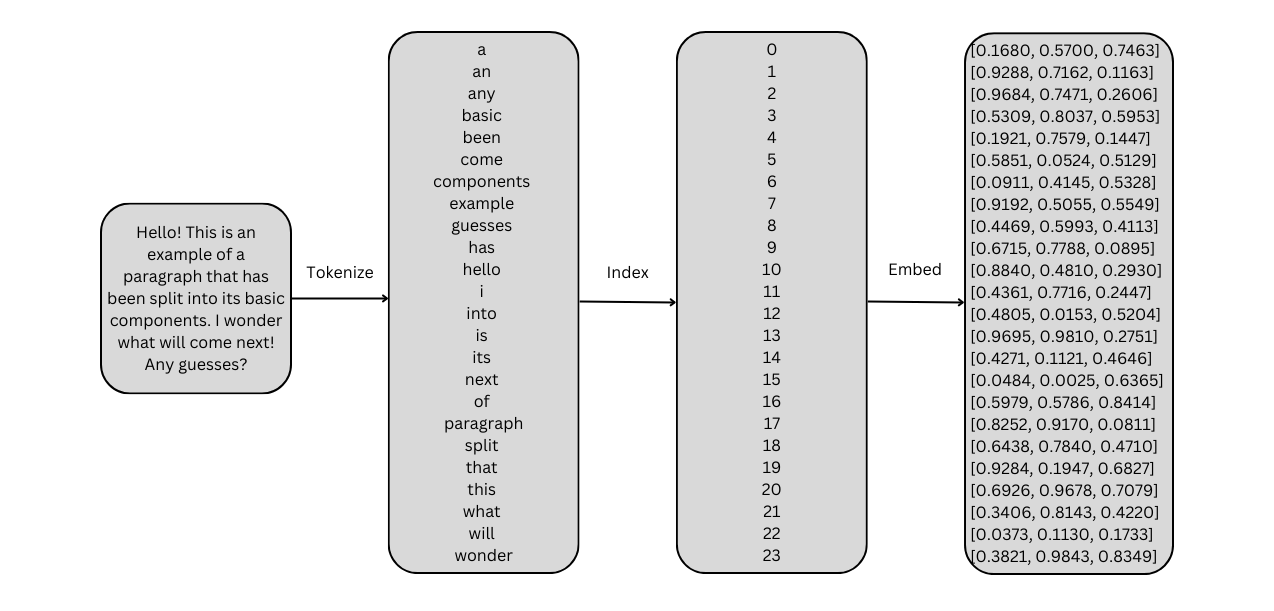

The most common method for mapping language into the embedding space is through tokenization and token embedding. A tokenizer maps a word or word fragment into a discrete token index, and an index-fetching embedding layer (implemented in frameworks like PyTorch with nn.Embedding) maps this index into a fixed-dimension embedding vector. In principle, all discrete features can be mapped into the embedding space using this approach.

Vector Quantization

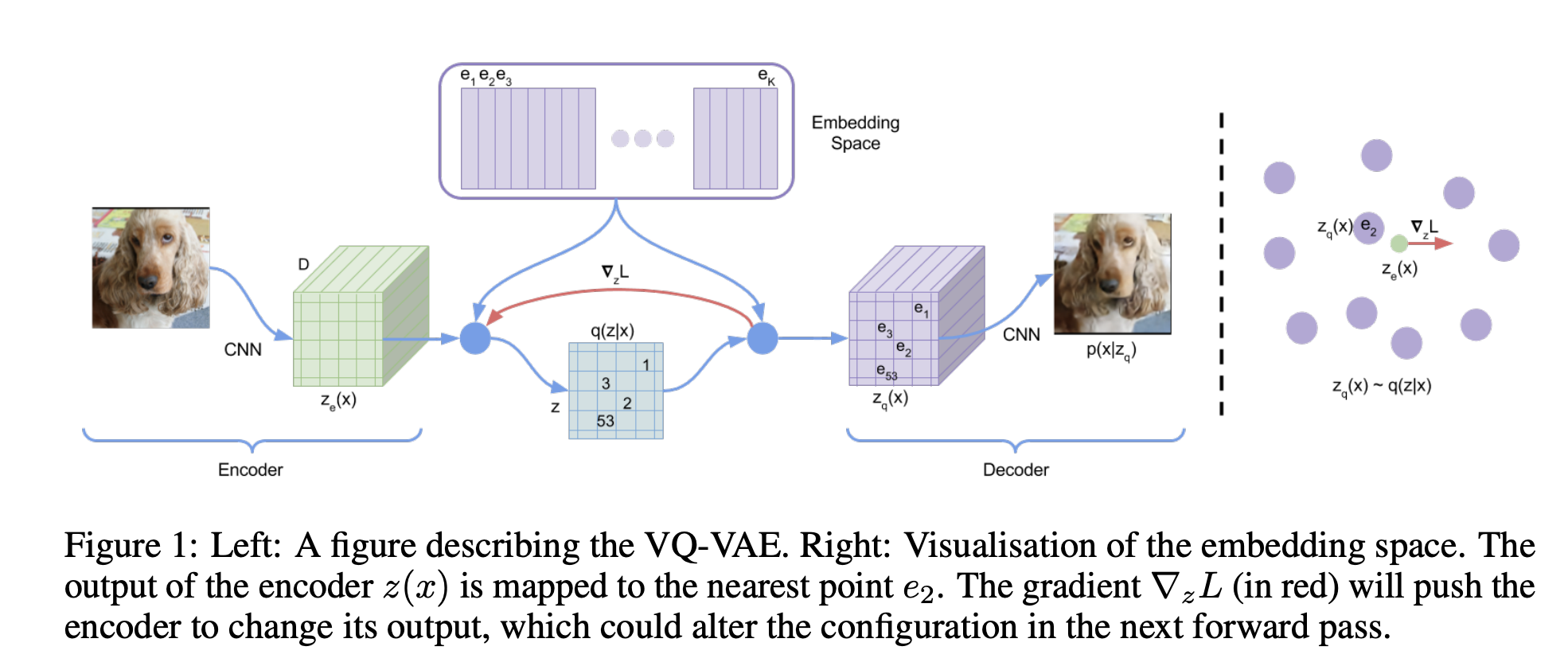

For continuous features, one intuitive approach is to first tokenize them into discrete tokens, thereby unifying the embedding process across both discrete and continuous features. Vector quantization, introduced in VQ-VAE, is one of the most common methods for this purpose.

Van Den Oord, Aaron, and Oriol Vinyals. "Neural discrete representation learning." NeurIPS, 2017.

Vector quantization maintains a "codebook" , which functions similarly to the index-fetching embedding layer, where is the total number of unique tokens, and is the embedding size. A given continuous vector is quantized into a discrete value by finding the closest row vector in to , and that row vector is fetched as the embedding for . Formally:

Lookup-Free Quantization

A significant limitation of vector quantization is that it requires calculating distances between the given continuous vectors and the entire codebook, which becomes computationally expensive for large-scale codebooks. This creates tension with the need for expanded codebooks to represent complex modalities such as images and videos. Research has shown that simply increasing the number of unique tokens doesn't always improve codebook performance.

“A simple trick for training a larger codebook involves decreasing the code embedding dimension when increasing the vocabulary size.” Source: Yu, Lijun, Jose Lezama, et al. “Language Model Beats Diffusion - Tokenizer Is Key to Visual Generation,” ICLR, 2024.

Building on this insight, Lookup-Free Quantization (LFQ) eliminates the embedding dimension of codebooks (essentially reducing the embedding dimension to 0) and directly calculates the discrete index by individually quantizing each dimension of into a binary digit. The index can then be computed by converting the binary representation to decimal. Formally:

For example, given a continuous vector , we first quantize each dimension into , based on the sign of each dimension. The token index of is simply the decimal equivalent of the binary 0110, which is 6.

However, this approach introduces another challenge: we still need an index-fetching embedding layer to map these token indices into embedding vectors for the Transformer. This, combined with the typically large number of unique tokens when using LFQ—a 32-dimensional will result in unique tokens—creates significant efficiency problems. One solution is to factorize the token space. Effectively, this means splitting the binary digits into multiple parts, embedding each part separately, and concatenating the resulting embedding vectors. For example, with a 32-dimensional , if we quantize and embed its first and last 16 dimensions separately, we “only” need to handle unique tokens.

Note that this section doesn't extensively explain how to map raw continuous features into the vector , as these techniques are relatively straightforward and depend on the specific feature type—for example, fully-connected layers for numerical features, or CNN/GNN with feature flattening for structured data.

Quantization over Linear Projection

You might be asking—why can't we simply use linear projections to map the raw continuous features into the embedding space? What are the benefits of quantizing continuous features into discrete tokens?

Although Transformers are regarded as universal sequential models, they were designed for discrete tokens in their first introduction in Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need". Empirically, they have optimal performance when dealing with tokens, compared to continuous features. This is supported by many research papers claiming that quantizing continuous features improves the performance of Transformers, and works demonstrating Transformers' subpar performance when applied directly to continuous features.

Mao, Chengzhi, Lu Jiang, Mostafa Dehghani, Carl Vondrick, Rahul Sukthankar, and Irfan Essa. “Discrete Representations Strengthen Vision Transformer Robustness,” ICLR, 2022.

Ilbert, Romain, Ambroise Odonnat, et al. “SAMformer: Unlocking the Potential of Transformers in Time Series Forecasting with Sharpness-Aware Minimization and Channel-Wise Attention,” ICML, 2024.

On the other hand, unifying different modalities into tokens is especially beneficial in the context of Transformer-based "foundation models," since it preserves the auto-regressive next-token prediction architecture of LLMs. Combined with special tokens such as "start of sentence" and "end of sentence," the Transformer model is flexible in generating contents of mixed modalities with varied length.

For example, by quantizing videos into discrete tokens and combining the token space of videos and language, one can create a unified Transformer model that generates both videos and language in one sequence. The start and end points of video and language sub-sequences are fully determined by the model, based on the specific input prompt. This structure would be difficult to replicate if we used tokenization for language but linear projection for videos.

Transformer Backbone

After different modalities are mapped into the same embedding space, they can be arranged into a sequence of embedding vectors and input into a Transformer backbone. We don't discuss the variations of Transformer structure and improvement techniques here, as they are numerous, and ultimately function similarly as sequential models.

Lan et al., “ALBERT”; Ye et al., “Differential Transformer”; Kitaev, Kaiser, and Levskaya, “Reformer”; Su et al., “RoFormer”; Dai et al., “Transformer-XL.”

As we know, the "full" Transformer structure proposed in Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need" includes an encoder and a decoder. They perform self-attention within their respective input sequences, and the decoder additionally performs cross-attention between its input sequence and the memory sequence derived from the encoder's output. Some early language models use encoder-only structure (like Devlin et al., "BERT") focused on outputting embedding vectors or encoder-decoder structure (like Chung et al., "Scaling Instruction-Finetuned Language Models") for generating natural language output. Most modern large language models and foundation models use decoder-only structure (like Brown et al., "Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners"), focusing on auto-regressive generation of language output.

The encoder-only structure theoretically excels at representation learning, and its produced embedding vectors can be applied to various downstream tasks. Recent developments have gradually moved towards decoder-only structure, centered around the idea of building models that are capable of directly generating the required final output of every downstream task.

For example, to perform sentiment analysis, BERT will compute an embedding vector for the query sentence, and the embedding vector can be used in a dedicated classifier to predict the sentiment label. GPT, on the other hand, can directly answer the question "what is the sentiment associated with the query sentence?" Comparatively, GPT is more versatile in most cases and can easily perform zero-shot prediction.

Nevertheless, representation learning is still a relevant topic. The general understanding is that decoder-only structure cannot perform conventional representation learning, for example mapping a sentence into a fixed-dimension embedding vector. Yet, there are a few works in the latest ICLR that shed light on the utilization of LLMs as representation learning or embedding models:

Gao, Leo, Tom Dupre la Tour, Henk Tillman, Gabriel Goh, Rajan Troll, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, Jan Leike, and Jeffrey Wu. “Scaling and Evaluating Sparse Autoencoders,” 2024. Link

Li, Ziyue, and Tianyi Zhou. “Your Mixture-of-Experts LLM Is Secretly an Embedding Model for Free,” 2024. Link

Zhang, Jie, Dongrui Liu, Chen Qian, Linfeng Zhang, Yong Liu, Yu Qiao, and Jing Shao. “REEF: Representation Encoding Fingerprints for Large Language Models,” 2024. Link

Output Layer

For language generation, Transformers typically use classifier output layers, mapping the latent vector of each item in the output sequence back to tokens. As we've established in the "modality embedding" section, the optimal method to embed continuous features is to quantize them into discrete tokens. Correspondingly, an intuitive method to output continuous features is to map these discrete tokens back to the continuous feature space, essentially reversing the vector quantization process.

Reverse Vector Quantization

One approach to reverse vector quantization is readily available in VQ-VAE, since it is an auto-encoder. Given a token , we can look up its embedding in the codebook as , then apply a decoder network to map back to the continuous feature vector . The decoder network can be pre-trained in the VQ-VAE framework—pre-train the VQ-VAE tokenizer, encoder, and decoder using auto-encoding loss functions, or end-to-end trained along with the whole Transformer. In the NLP and CV communities, the pre-training approach is more popular, since there are many large-scale pre-trained auto-encoders available.

.png)

Efficiency Enhancement

For continuous feature generation, unlike language generation where the output tokens are the final output, we are essentially representing the final output with a limited size token space. Thus, for complicated continuous features like images and videos, we have to expand the token space or use more tokens to represent one image or one video frame to improve generation quality, which can result in efficiency challenges.

There are several workarounds to improve the efficiency of multi-modal outputs. One approach is to generate low-resolution outputs first, then use a separate super-resolution module to improve the quality of the output. This approach is explored in Kondratyuk et al., "VideoPoet" and Tian et al., "Visual Autoregressive Modeling". Interestingly, the overall idea is very similar to nVidia's DLSS, where the graphics card renders a low-resolution frame (e.g., 1080p) using the conventional rasterization pipeline, then a super resolution model increases the frame's resolution (e.g., 4k) utilizing the graphics card's tensor hardware, improving games' overall frame rate.

Another workaround follows the idea of compression. Take video generation as an example. The model generates full features for key frames, and light-weight features for motion vectors that describe subtle differences from those key frames. This is essentially how inter-frame compressed video codecs work, which takes advantage of temporal redundancy between neighboring frames.

.png)

Fuse with Diffusion Models

Despite continuous efforts to enable representation and generation of images and videos with a language model structure (auto-regressive), current research indicates that diffusion models (more broadly speaking, score-matching generative models) outperform language models on continuous feature generation. Score-matching generative models have their own separate and substantial community, with strong theoretical foundations and numerous variations emerging each year, such as stochastic differential equations, bayesian flow, and rectified flow. In conclusion, score-matching generative models are clearly here to stay alongside language models.

An intriguing question arises: why not integrate the structures of language models and diffusion models into one Transformer to reach the best of both worlds? Zhou et al. in "Transfusion" explored this idea. The approach is straightforward: build a Transformer that can handle both language and image inputs and outputs. The language component functions as a language model, while the image component serves as a denoiser network for diffusion models. The model is trained by combining the language modeling loss and DDPM loss, enabling it to function either as a language model or a text-to-image denoiser.

.png)

Conclusion

In conclusion, the evolution of Transformers into versatile foundation models capable of handling multiple modalities and functionalities represents a significant advancement in AI research. By enabling a single architecture to process diverse data types through techniques like vector quantization and lookup-free quantization, researchers have created models that can seamlessly integrate language, images, and other modalities within the same embedding space.

In our research domain, we encounter even more diverse and domain-specific multi-modal data, such as traffic flows, trajectories, and real-world agent interactions. A unified Transformer for such data presents a promising solution for creating "foundation models" that generalize across diverse tasks and scenarios. However, domain-specific challenges, including data encoding and decoding, computational efficiency, and scalability, must be addressed to realize this potential.